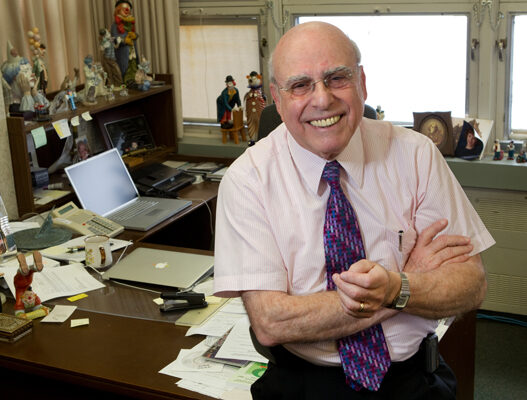

Dr. Phil Gold: The Ride of a Lifetime

Over the past six decades, Dr. Gold’s accomplishments in cancer and immunology research, clinical practice, hospital administration, and teaching have become the stuff of legend. At the age of 84, he has accumulated more letters than the alphabet behind his name and more awards and accolades than he can list from memory. Back in 1961, though, Dr. Gold was a first-year resident at the Montreal General Hospital who was deeply grieved at the ravages of cancer. “I saw so many patients who were suffering, and all we could do for them was fill them with radiation, drugs, and hope,” Dr. Gold remembers. “I thought there had to be a better way.”

Finding a Needle in a Haystack

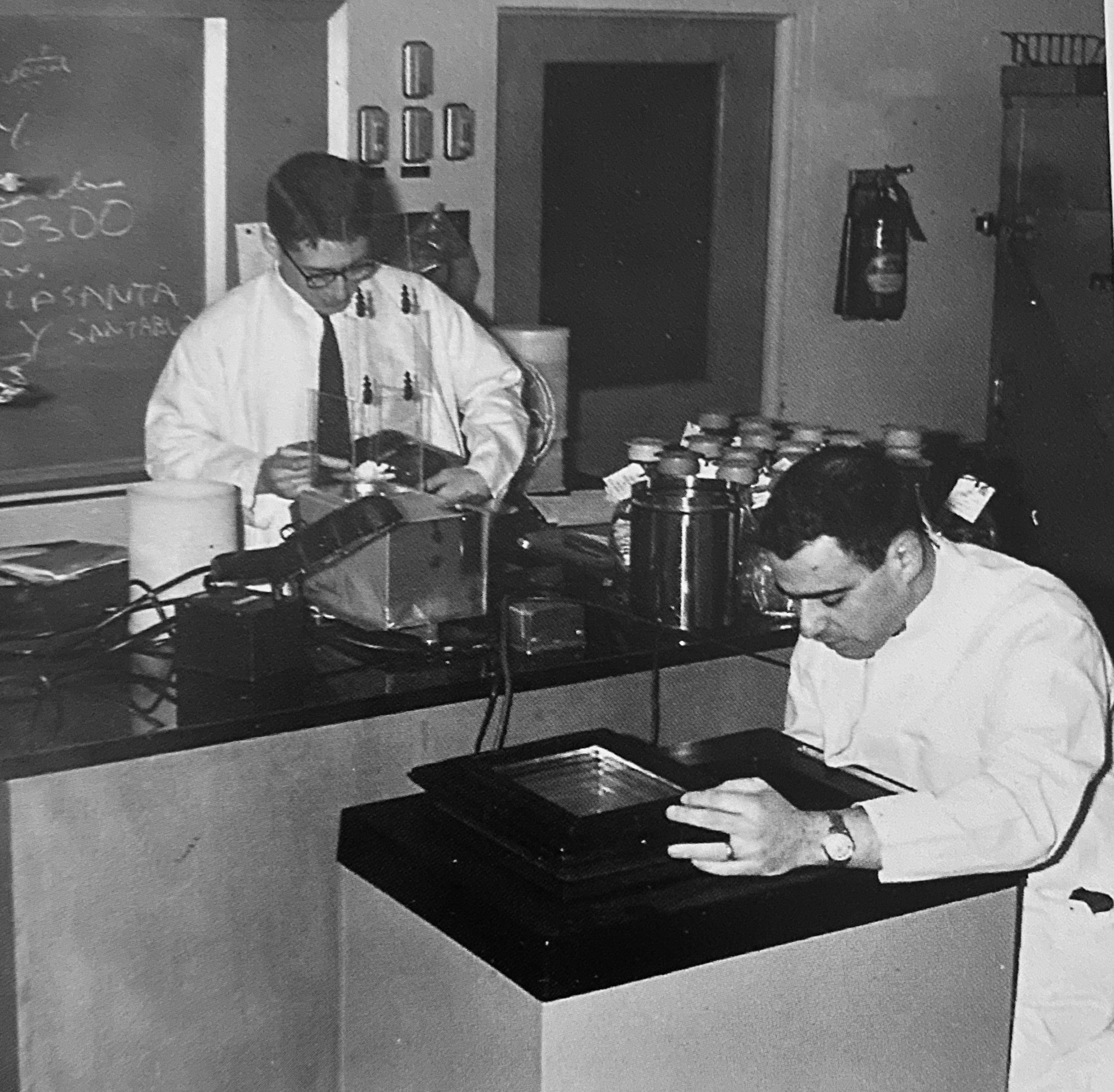

In 1963, Dr. Gold embarked on a PhD in physiology in the laboratory of Dr. Samuel Freedman, a clinical immunologist who would later serve as Dean of the McGill Faculty of Medicine from 1977 to 1981. His career trajectory shifted dramatically when he came across a paper on immunologic tolerance and hatched a plan to induce tolerance to normal human bowel tissues in a newborn rabbit.

Dr. Gold’s unusual experiment succeeded beyond anyone’s wildest dreams. He successfully induced tolerance to normal human bowel tissues in newborn rabbits, injected them with human colon cancer cells as adults, and searched for any differences in how the rabbits’ immune systems reacted to cancer cells compared to normal cells. He found what he was looking for: carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), a protein that indicates the presence of cancer.

Once the word began to spread, Dr. Gold’s career took flight. The paper he co-authored was the most highly cited in the medical literature at one point in time, and the FDA soon recognized CEA as the first human tumour marker for cancer. To this day, clinicians use a CEA blood test to diagnose and manage certain types of cancer, particularly cancers of the large intestine and rectum. According to Dr. Abraham Fuks, another renowned McGill immunologist who previously served as Dean of the Faculty of Medicine, Dr. Gold achieved a rare feat. “Not many lab tests innovated in 1965 are still used clinically today,” says Dr. Fuks. “This is what happens when highly ambitious, talented people find ways to execute a creative idea.”

The Grandfather of Cancer Research

Dr. Gold and his colleagues leveraged the discovery of CEA to write a new chapter in cancer research and clinical care. In 1978, Dr. Gold accepted a role as the first director of the newly inaugurated McGill Cancer Centre, which evolved over time into the world-class Rosalind and Morris Goodman Cancer Research Centre. “People like Dr. Gold saw the future,” says Dr. David Eidelman, the current Dean of the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences at McGill University. “Unlike most people of his time, he approached cancer as a subject of mechanistic inquiry instead of this mysterious, hopelessly untreatable disease.”

The discovery of CEA has given rise to more than a few scientific careers over the years. Dr. Nicole Beauchemin, a principal investigator at the Goodman Cancer Research Centre, calls herself the “scientific granddaughter” of Dr. Gold. “With the discovery of CEA, he opened up a new field of research and inspired dozens of research teams to build upon his work,” she says.

In 1986, Dr. Beauchemin contributed her experience in molecular biology and cloning to a Cancer Centre project designed to clone the CEA gene. She and other researchers went on to discover nearly 30 more genes that all relate in some way to the original CEA protein. By using these proteins as markers to track, treat, and understand cancer cells, they can develop targeted therapies based on gene expression profiles.

Untrammeled Optimism

In 1980, Dr. Gold returned to the Montreal General Hospital as Physician-in-Chief. Dr. Christos Tsoukas, who has served as Director of the Division of Clinical Allergy and Immunology at the McGill University Health Centre (MUHC) since 2007, was a resident when Dr. Gold made his return. “Dr. Gold would go out of his way to relate to residents with enthusiasm and collegiality, and that’s an attitude that continues today through all of the directors and division leaders who were once residents,” remembers Dr. Tsoukas. “He has always encouraged, not dictated, while maintaining a healthy sense of humour.”

When Dr. Gold became Physician-in-Chief at the Montreal General, his enthusiasm for the role was put to the test when he encountered a dire financial situation. “I went to the cupboard, and the cupboard was bare,” he says. “We had no money to do what we needed to do.” Nevertheless, what strikes people most when they work with Dr. Gold in any capacity is his “untrammeled optimism,” says Dr. Fuks. Even in the bleakest funding environments, Dr. Gold could be so unrelentingly optimistic that he could come across as unrealistic at times. Ultimately, his sunny outlook played an instrumental role in persuading donors to give generously and staff to economize willingly. By the time he stepped down in 1995 to become the Executive Director of the Clinical Research Centre at the MUHC, the cupboard was full again.

Leaving a Legacy

It is hard to overstate the impact of Dr. Gold on the past 50 years. He still gives guest lectures when invited, and he is satisfied with the legacy he leaves behind as he eases into a well-earned retirement. “That legacy is my students, my children, and my grandchildren, who have all gone on to do great things,” he affirms. “Now it’s their turn to carry the mantle. I’ve had the ride of a lifetime, and I’m grateful for it.”